Around the same time of hearing about FYM, I had just published a paper in Proceedings B about how wild birds maintain their positions within social networks following experimental removal of their associates. Almost simultaneously, a paper was published in Nature Human Behaviour showing how Facebook interaction social networks appear resilient to the loss of a user. So, as my paper had some parallels with humans (i.e. how individuals can compensate for losing their ‘friends’ through creating new social ties), and also provided a forum for considering a real-world biodiversity problem (i.e. how natural animal populations respond to losing individuals), I felt like it’d be great if this could be made available to ‘young minds’ in the form of a child-friendly version of the paper. Almost all science has aspects that would be of interest to the next generation (and if not, you might need to ask why)! But, in the same sense, original scientific research manuscripts are one of the furthest possible pieces of text away from the usual reading material for children. In the case of this paper, network analysis is a relatively complicated process, and the conclusions drawn (in relation to how our predictions of dynamic social systems’ responses to perturbations may be altered given our results) were perhaps not straightforward for lay reading, nor innately exciting to children. Therefore, although I really liked to idea of making this primary research accessible to kids, it also felt daunting. Fortunately, a couple of years earlier (around the same time FYM began), I carried out a masterful anticipatory tactic for future school-children science communications opportunities: I married a primary school teacher (Sarah). Of course, a couple of other reasons played into this decision (having been together since being school kids ourselves was one of them), but now it was about to pay off for this reason too. I should point out that marrying a primary school teacher isn’t a requirement for publishing in FYM. Most people I know have a teacher as a friend that they could potentially rope into the process if desired. But, in fact, the majority of papers in FYM are carried out exclusively by researchers (with help from the FYM handlers and editors – as discussed later). However, admittedly in this case, I found that involving Sarah was extremely useful, as she carried out most of the heavy lifting in terms of initially drafting the child-friendly version of the manuscript, and did so in less than a day (I imagine it would have been much more time-consuming for me). So it’s certainly most useful to listen to Sarah for this part of the process: The Writing: A Teacher’s Perspective Sarah: “On a personal level, I have always had a great interest in nature and biological sciences. I grew up with enthusiasm for all things animal and enjoyed all nature- based activities. From a teacher’s perspective, I think it is fair to say that science is widely enjoyed by both teachers and pupils alike. It tends to be a subject which lends itself to more of a practical approach which is exciting to teach and in turn inspiring when taught. However, there is a definite need in schools to push the notion of the ever changing, growing aspect of science. Children need to understand that what we know in science is in fact what we know ‘now’ in science. I believe this idea only increases the appeal for children as they are natural investigators. FYM is an amazing platform for this message. The idea that children can read about new scientific research at the same time as adults and professionals is astounding and inspiring. It gives children a wider sense of science. Here are a few of the tips that I shared with Josh when we worked on the paper together:

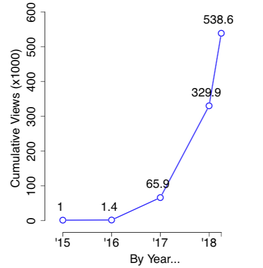

The Process At the time of drafting our child-friendly version of the manuscript, only a couple of articles had been published in the Biodiversity section of Frontiers for Young Minds by this point. To kick off the process, I sent a brief pre-submission enquiry to the Head Editor of the Biodiversity section, Prof. Chelsea Specht. This comprised of a brief description of the original research manuscript, the reasons why it may be suitable for FYM, and a short child-friendly summary (basically the proposed abstract). Prof. Specht was extremely helpful and friendly, and provided some initial advice and showed enthusiasm for the article. This encouraged us to put together a polished version of the text, along with the figures, and submit it in the same way that most other manuscripts are submitted. However, the following part was much more fun that the usual paper revision process! The paper is assigned to an associate editor, and this one was passed to Prof. Sophie der Heyden who again was especially supportive and welcoming. The associate editor chooses the ‘young reviewers’, which is definitely one of the best parts about FYM. This can consist of either a classroom of children, or a few individual kids. Either way, using the young reviewers themselves as quality control for the journal is an excellent idea, and the resulting reviews are tremendous. Admittedly I was partly apprehensive due to the examples of comments I’d come across for other papers, such as: “I really liked figure 1 and 2. Didn’t really pay attention to figure 3, it didn’t help anyway.” – Age 12 and the dreaded question across sciences... “Why did you decide to write this article?” – Age 11 along with probably something we’ve all thought at least once while reviewing a paper… “This seems important, but the way it is written is so boring I can’t even get to the end. Could the authors maybe sound excited about what they are doing?” – Age 12 But, in fact, getting the reviews was very rewarding and inspiring, and showed just how insightful the children are. Highlights from the comments about our paper were: “This discover is important because it is important as it helps us to learn more about the birds and we can use the research to think about other animal species reactions to loosing members of their community.” – Age 10 And – “It was about how animals (in this case birds) cope when losing a flock member. The information is about how they act if they loose a flock member. The authors also showed the difference between taking away a bird for long periods and also releasing the birds again almost immediately.” – Age 13 Along with the young reviewers, the manuscripts are also assigned an adult ‘scientific mentor’ who takes the role of a particularly amicable version of a usual reviewer, and flags up the changes that need to be made. After revising the article, a final specialist proof-reader will ensure all the language is child-friendly, and you’ll also have an illustrator provide a colourful illustration for your paper (which I’ll certainly be using for future presentations!). What are you waiting for? In sum, I’d definitely recommend you put together a FYM article about your most exciting recent research. If the altruistic prospect of providing children with free and suitable access to the scientific literature isn’t enough for you, hopefully the selfish gains of the fun of the article publication and illustrations at no cost, getting the young reviewers comments, and drawing further attention to your research (our FYM article had >1000 views in just the first week, and equivalent twitter attention of most of my primary research articles), should convince you. If you’re now hooked and looking for more details, check out the brief summary article in Neuron written by Sabine Kastner and Robert Knight (the founder), along with the information on the website. Obviously, if you have any questions or if you think Sarah or myself can help you in anyway, please feel free to get in touch. We look forward to seeing your Frontiers for Young Minds article soon!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|