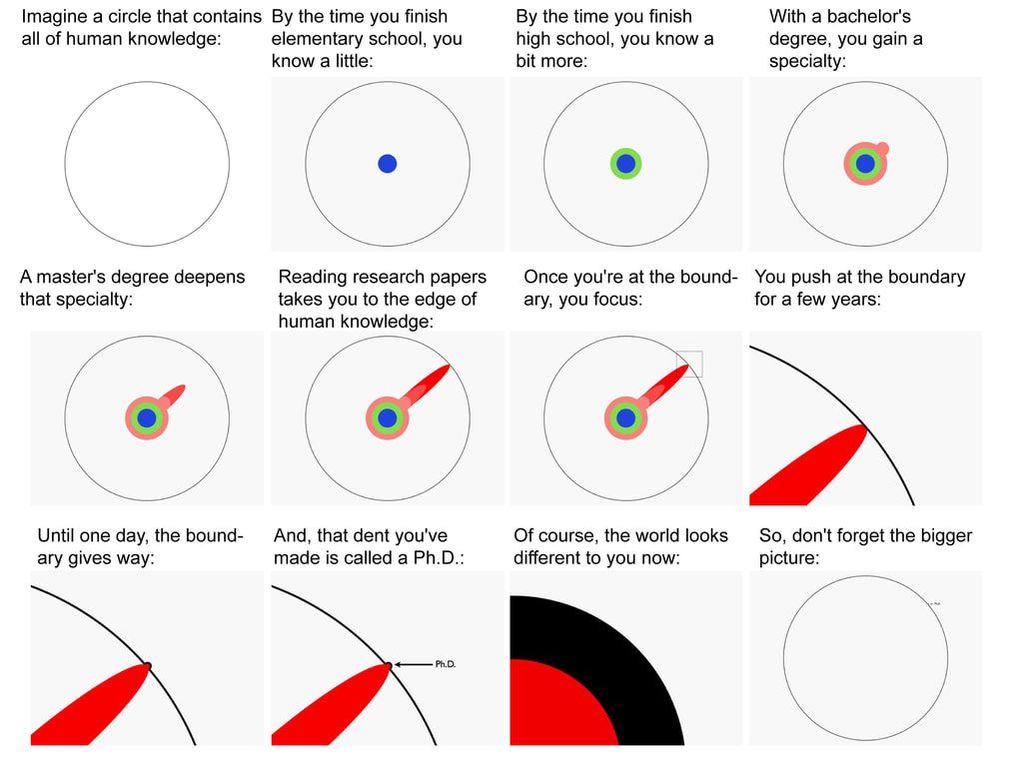

Most of us start our PhDs convinced that we will solve a major problem in biology—Why do animals cooperate? How do juveniles disperse? Or, in my case, why do birds join mixed-species flocks? The answer will be obvious once I have collected the amazing data outlined in my research proposal. However, at some point during the PhD it becomes clear that the results of our research will fall short, often by a very long way, of our ambitions. This realisation can be very sudden, and invariably lead to extreme disillusion. Matt Might best captured the reality of what a PhD is with his illustrations showing that the advances made by most PhD projects are usually infinitely small: I have personally felt this disappointment. In fact I would be surprised if any PhD student hasn’t. More seriously, I have also seen the disappointment from this steer otherwise talented students out of academia, or at least cause them extensive periods of stress, depression, or anxiety. But why does it happen? One reason is that we typically think that the research we are personally doing is of utmost importance. This idealism around our work is important, as we need to have the motivation to persevere through endless hours of data collection, draft writing, handling comments from co-authors, etc. However, the excitement might not be shared by others in our community (who have their own super-important research). A second reason is that we are trained from the start of our studies to aim for big questions. For many of us, the PhD begins by writing a detailed research proposal. The aim of this proposal is for the student to outline a clear plan which will convince a committee that the research is feasible. However, a big part of this proposal has become ‘the sell’.

Publishing papers and publishing them in high impact journal is becoming more and more important for success. Thus, even at the start of a PhD we are already under pressure to identify impact. That is, “what is the big question” or “identify the gap”. I think it’s great to be encouraged to think about the big picture—such as making sure students know the major influential theories. However, it is important to remember (or remind students) that we can, at best, collect data to support theories (or not). Hopefully a good committee will already be tempering expectations at the proposal stage (both in terms of goals but also in terms of the amount of work one plans to achieve). Awakening to the reality only at the point when data start coming in, or worse when writing up, in can be too much to bear for some students. What steps can you take to avoid disappointment? The first step is to manage the expectation for how much can be done during a PhD. When your committee hints that you might have too many chapters planned, take them seriously. What really helps here is to make timelines. Start with a detailed timeline for the next few months (weekly milestones), then one for the next year (monthly milestones), and finally major milestones for upcoming years. While it may seem a pain to do and a waste of your time now, it is the best way to learn for yourself how long it takes you to do the work you have planned, and ultimately how much you can achieve. The second step is to manage expectations for how much a PhD chapter actually contributes to broader scientific knowledge. The best way to do this is to critically evaluate papers that are coming out in the journals central to your discipline. Don’t look to Science or Nature here, but look to the journals of the societies to which you could (should) be a member. What is the contribution of these papers? Remember that they will most likely be over-selling the quality and the importance of their work. If you are having trouble with evaluating the importance of the contribution of work in these journals, then suggest a paper for a journal club (if you are lucky to have one – otherwise why not start a journal club?). On the topic of Science or Nature, it might seem like everyone has published a paper in there recently. However, this is purely an illusion. Third, start with data analysis early. It’s only by forcing yourself to generate real results that the actual scope of your research can really be clarified. Analysing data as it is being collected is also hugely useful for identifying potential problems that you might not have foreseen, which by fixing might improve the impact of your work. Also remember that collecting lots of data on lots of things isn’t what makes the greatest contribution, but showing something very convincingly does goes a long way, so be strategic with your work. Further, analysis can easily take as long as collecting the data – even when it is relatively simple (I’ll write more on this in a later post). Finally, remember that a PhD is a very short time (at least for us in Europe). Don’t compare what you’ve achieved in your first few years to what others have achieved in an entire career. It often takes many years and many experiments’, worth of experience to show something with the simplicity and elegance that results in truly innovative findings. So don’t give up yet!

1 Comment

Robert Kraus

20/7/2018 02:48:16 pm

On the shoulders of giants...

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

|